Robert Adler: Making Life Safe for Couch Potatoes

by Michael Daisy

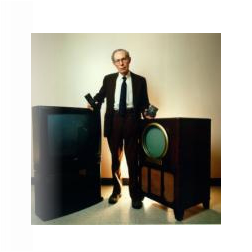

Robert Adler invented the remote control.

If not for the estimable work of Robert Adler, the simple act of watching TV - that ubiquitous appliance considered an essential part of every home - would be very different from the experience to which we've become accustomed. Without Adler's contributions, not only might the act of watching the tube be very different, the TV-itself might still be a small, funny-looking box with tinny sound.

Dr. Robert Adler died in February of heart failure in Boise, Idaho. He was 93. During his long, engineering career (mostly with Zenith Electronics Corporation), Dr. Adler published dozens of technical papers and, was granted more than 180 U.S. patents for his pioneering efforts in the field of television.

Adler is best remembered as the co-inventor of the TV remote control, the clicker, an invention for which he and Eugene Polley were awarded an Emmy from the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences.

Dr. Adler didn't believe the remote control represented his most significant contribution to television technology. Perhaps not, but history has established that the remote is indeed significant because of how it has affected the way things are designed, and altered the way we do things. If you don't believe that, try to remember the last time you stood in front of your TV at home and physically pushed buttons to turn it on or off or change the station.

Considering the Remote

Like most new technological developments, the remote control was developed for use with military applications in mind. The Germans developed a remote-controlled boat that was used to ram enemy ships in the First World War. The Allies employed remote controlled bombs and other devices in the second.

The history of the TV remote control began with Commander Eugene F. McDonald, Jr., founder and first president of Zenith Radio Corporation. McDonald - who acquired the "Commander" title legitimately as a U.S. Naval officer in intelligence during the First World War - was the impetus behind the introduction of the first TV remote control in 1950.

It wasn't a magnanimous gesture. Neither was McDonald motivated by a desire to make life easier for TV viewers. He hated commercials. He believed that free TV, AKA commercial TV, was bad business. By encouraging viewers to change channels to avoid commercials McDonald hoped to convince the fledgling TV broadcast industry to abandon commercially-sponsored TV in favor of commercial-free, pay TV. "He thought advertiser-supported television would never fly," said Zenith corporate historian John Taylor.

Enter Lazy Bones.

The Lazy Bones was a primitive affair that added considerably (the equivalent of about $355 today) to the cost of a TV. It consisted of two buttons, one for power on/off, the other changed stations. What set this remote apart from today's remote controls was the cable that connected it to a motor in the TV that performed the action.

Remember, this was the early ‘50s, and TVs were largely mechanical devices.

People liked the idea of being able to control the set from across a room. They didn't, however, like the cable. Not only was it unsightly, it was dangerous. People tripped over it. That made it potentially costly for Zenith.

The Commander ordered his engineers to devise a solution.

In 1955, one of Adler's colleagues, Eugene Polley, was first. Polley - an ambitious college dropout, who began with Zenith in 1935 as a stock boy before finessing his way into the engineering department - invented the "Flashmatic," the first wireless, TV remote control.

Zenith gave Polley, who received 18 patents during his career, a $1,000 bonus for his invention.

The "Flashmatic" was a glorified (albeit, very directional) flashlight the viewer used to turn the set on or off, control the volume, and change stations. Photo cells were located at each corner of the picture tube, and viewers made things happen by pointing the light at the appropriate corner of the set.

The "Flashmatic's" shortcomings became apparent soon after it was introduced because of its reliance on visible light. If exposed to direct sunlight, the TV might begin to scroll uncontrollable through the channels, make weird sounds, and otherwise take on a life of its own. If the batteries were low, people had a tendency to believe the set was broken.

McDonald's engineering team next tried sound. That, too, proved problematical as sympathetic noises generated in other rooms or outdoors, by household appliances, and even from the TV program itself, could trigger unwanted results.

It was Dr. Adler's suggested use of high-frequency sound, or ultrasonics, that led to the introduction of what is considered the first practical, wireless, TV remote.

Zenith's "Space Command" was introduced in the fall of 1956. Based on Adler's idea, it used four buttons to control: power, sound, channel up, and channel down. Each of its four aluminum rods - measuring roughly two-and-one-half-inches - vibrated at a different frequency when struck by a tiny trigger-like device.

The "Space Command" used no batteries. That was its principal advantage. On the other hand, it used an elaborate receiver that required six vacuum tubes to process sound signals, and added roughly 30-percent to the cost of the TV. Still, it worked well enough.

Dr. Adler's "Space Command" concept worked well enough to survive into the 1980s when remotes that used infrared light were introduced. During the quarter century that ultrasonic technology was king, something in the neighborhood of nine million TVs, produced by Zenith and other manufacturers, were sold.

In response to charges that his invention contributed to the obesity crisis in America by creating generations of couch potatoes, Dr. Adler was unapologetic. He told the Associated Press in 1996 that, "I don't take responsibility for couch potatoes. They really should exercise."

Coming to America

Dr. Robert Adler was born on December 4, 1913 in Vienna, Austria to Max Adler, a prominent social theorist, and Jenny Hershmann Adler, a doctor. He received his doctorate in physics at the age of 24 from the University of Vienna in 1937.

Following Austria's annexation by Germany in 1939, Dr. Adler, a Jew, left the country. He traveled first to Belgium, then to England, where he acted on the advice of friends, who recommended that he emigrate to the United States.

Adler arrived in the U.S. in 1941, at which time he was hired by Zenith (known at the time as the Zenith Radio Corporation) to work in its research division. It was a common practice for companies like Zenith and RCA to fund their own state-of-the-art research facilities that were the equal of facilities such as AT&T's Bell Laboratories.

He settled in Chicago where the company maintained headquarters. He remained in Chicago the rest of his life, and continued to work for Zenith on and off for the next six decades.

In 1952, Adler was named associate research director. In 1963, he was named vice president and director of research. He retired in 1982, but continued to work for Zenith as a technical consultant until 1999 when Zenith was purchased by LG Electronics of South Korea.

According to John Pederson, a former Zenith vice president, Dr. Adler was not allowed to work on classified projects during the Second World War. So, the company set him up in a private laboratory with assistants to work independently on projects of his own choosing.

Despite the prohibitions that kept him from working on classified, wartime projects, Dr. Adler specialized in military communications equipment, and he came to be appreciated for his ability to see the wider applications of specific technology. Most of his later work, including the ultrasonic technology employed in the "Space Command" remote, grew out of his early research.

Peace

Adler concentrated his efforts on television technology after the war. His invention of the "gated-beam" vacuum tube was typical of the innovations that sprang from his fertile mind.

(Incidentally, the "gated-beam" tube was Dr. Adler's personal choice for the most significant innovation of his long and distinguished career.)

The "gated-beam" tube represented an entirely new concept in receiving tubes and sound circuitry. Not only did it improve sound quality by eliminating a lot of spurious noise and distortion, it simplified the design of sound systems in TV receivers, and reduced costs.

The electron beam parametric amplifier was another significant advance. Jointly developed in 1958 by Dr. Adler and Dr. Glen Wade of Stanford University, the amplifier was universally adopted by radio astronomers worldwide, as well as by the U.S. Air Force for long-range missile detection.

In 1966, Dr. Adler's work in acousto-optical interaction was behind the successful public demonstration during which a wall-sized television display was generated by, what was then, unconventional means. In place of a cathode ray tube, the team of Zenith engineers created the display by manipulating a laser beam.

In the early 1970s, Dr. Adler's research was instrumental in the development of the digital video revolution that exploded in the 1990s.

In recent years, he had been a prime mover behind the evolution of touch screens as a result of his work involving surface acoustic wave (SAW) technology, and as a consultant to firms such as Elo TouchSystems, a leading manufacturer of interactive touch screens at airport kiosks, museums, and elsewhere.

SAW technology is an integral part of a wide range of uses from television to video gaming to automated teller machines, and more. The technology is essential to our love-hate relationship with the cellular telephone.

Dr. Adler's research into SAW technology continued to the end of his life. His most recent patent application dealt with touch-screen technology and was published two weeks before he died.

Honors and Awards

A listing of the honors bestowed on Dr. Adler follows. By no means is it complete:

1951 - Elected Fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc. (IEEE) "for his development of transmission and detection devices for frequency modulated signals and of electro-mechanical filter systems."

1959 - Awarded the 1958 Outstanding Technical Achievement Award from IEEE for his "original work on ultrasonic remote controls" for television.

1967 - Awarded "Inventor-Of-The-Year" award by George Washington University's Patent Trademark and Copyright Research Institute "for his inventions in the field of electronic products, devices, and systems used in aircraft communications, radar, TV receivers and FM broadcasting."

1970 - Received the Consumer Electronics Outstanding Achievement Award, an honor given annually for significant contributions to the advancement of consumer electronics through engineering achievements.

1980 - Received the Edison Medal, the IEEE's principal award for recognition of career meritorious achievement.

1981 - Received Sonics and Ultrasonics Achievement Award from IEEE.

1998 - Co-Recipient (with Eugene Polley) of the Engineering Emmy Award from the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences for "pioneering work in the development of the remote control."

2000 - Inducted into the Consumer Electronics Hall of Fame by the Consumer Electronics Association for significant contributions to the consumer electronics industry.

2000 - Inducted into the National Academy of Arts and Sciences Chicago/Midwest Chapter's "Silver Circle" in recognition of individuals who have devoted 25 years or more to the television industry, and for significant contributions to Chicago broadcasting.

He was also a Fellow in The American Association for the Advancement of Science, as well as a member of The National Academy of Engineering.

He was uncommonly modest. In 1969, he was sent to Moscow as part of an IEEE delegation to the annual meeting of the Popov Society for Radioengineering, Electronics, and Communications. Prior to going he learned Russian in order to be able to present his paper in Russian as a gesture of goodwill to his hosts.

A Full and Complete Life

In his personal life, Dr. Adler immersed himself in the Chicago cultural scene. He supported the Art Institute of Chicago, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Masters of Baroque, and Community Theater.

For years, he ventured whenever possible to the Rockies to engage in mountain hiking during summer months, and skiing in winter. He was an avid downhill skier until the age of 89. He was a licensed pilot and an enthusiastic world traveler for both business and pleasure. Dr. Adler was fluent in English, German, and French.

Dr. Adler had no children. He is survived by his wife, Ingrid Adler, whom he married in 1998. His first wife, Mary, died in 1993.

Mike Daisy

AmericanInventorSpot.com

Sources:

American National Business Hall of Fame

Associated Press

Chicago Tribune

The Dead Media Project

Federal Reserve Bank

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The New York Times

Yahoo

Widescreen Review

Wikipedia

Zenith Corporation

If not for the estimable work of Robert Adler, the simple act of watching TV - that ubiquitous appliance considered an essential part of every home - would be very different from the experience to which we've become accustomed. Without Adler's contributions, not only might the act of watching the tube be very different, the TV-itself might still be a small, funny-looking box with tinny sound.

Dr. Robert Adler died in February of heart failure in Boise, Idaho. He was 93. During his long, engineering career (mostly with Zenith Electronics Corporation), Dr. Adler published dozens of technical papers and, was granted more than 180 U.S. patents for his pioneering efforts in the field of television.

Adler is best remembered as the co-inventor of the TV remote control, the clicker, an invention for which he and Eugene Polley were awarded an Emmy from the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences.

Dr. Adler didn't believe the remote control represented his most significant contribution to television technology. Perhaps not, but history has established that the remote is indeed significant because of how it has affected the way things are designed, and altered the way we do things. If you don't believe that, try to remember the last time you stood in front of your TV at home and physically pushed buttons to turn it on or off or change the station.

Considering the Remote

Like most new technological developments, the remote control was developed for use with military applications in mind. The Germans developed a remote-controlled boat that was used to ram enemy ships in the First World War. The Allies employed remote controlled bombs and other devices in the second.

The history of the TV remote control began with Commander Eugene F. McDonald, Jr., founder and first president of Zenith Radio Corporation. McDonald - who acquired the "Commander" title legitimately as a U.S. Naval officer in intelligence during the First World War - was the impetus behind the introduction of the first TV remote control in 1950.

It wasn't a magnanimous gesture. Neither was McDonald motivated by a desire to make life easier for TV viewers. He hated commercials. He believed that free TV, AKA commercial TV, was bad business. By encouraging viewers to change channels to avoid commercials McDonald hoped to convince the fledgling TV broadcast industry to abandon commercially-sponsored TV in favor of commercial-free, pay TV. "He thought advertiser-supported television would never fly," said Zenith corporate historian John Taylor.

Enter Lazy Bones.

The Lazy Bones was a primitive affair that added considerably (the equivalent of about $355 today) to the cost of a TV. It consisted of two buttons, one for power on/off, the other changed stations. What set this remote apart from today's remote controls was the cable that connected it to a motor in the TV that performed the action.

Remember, this was the early ‘50s, and TVs were largely mechanical devices.

People liked the idea of being able to control the set from across a room. They didn't, however, like the cable. Not only was it unsightly, it was dangerous. People tripped over it. That made it potentially costly for Zenith.

The Commander ordered his engineers to devise a solution.

In 1955, one of Adler's colleagues, Eugene Polley, was first. Polley - an ambitious college dropout, who began with Zenith in 1935 as a stock boy before finessing his way into the engineering department - invented the "Flashmatic," the first wireless, TV remote control.

Zenith gave Polley, who received 18 patents during his career, a $1,000 bonus for his invention.

The "Flashmatic" was a glorified (albeit, very directional) flashlight the viewer used to turn the set on or off, control the volume, and change stations. Photo cells were located at each corner of the picture tube, and viewers made things happen by pointing the light at the appropriate corner of the set.

The "Flashmatic's" shortcomings became apparent soon after it was introduced because of its reliance on visible light. If exposed to direct sunlight, the TV might begin to scroll uncontrollable through the channels, make weird sounds, and otherwise take on a life of its own. If the batteries were low, people had a tendency to believe the set was broken.

McDonald's engineering team next tried sound. That, too, proved problematical as sympathetic noises generated in other rooms or outdoors, by household appliances, and even from the TV program itself, could trigger unwanted results.

It was Dr. Adler's suggested use of high-frequency sound, or ultrasonics, that led to the introduction of what is considered the first practical, wireless, TV remote.

Zenith's "Space Command" was introduced in the fall of 1956. Based on Adler's idea, it used four buttons to control: power, sound, channel up, and channel down. Each of its four aluminum rods - measuring roughly two-and-one-half-inches - vibrated at a different frequency when struck by a tiny trigger-like device.

The "Space Command" used no batteries. That was its principal advantage. On the other hand, it used an elaborate receiver that required six vacuum tubes to process sound signals, and added roughly 30-percent to the cost of the TV. Still, it worked well enough.

Dr. Adler's "Space Command" concept worked well enough to survive into the 1980s when remotes that used infrared light were introduced. During the quarter century that ultrasonic technology was king, something in the neighborhood of nine million TVs, produced by Zenith and other manufacturers, were sold.

In response to charges that his invention contributed to the obesity crisis in America by creating generations of couch potatoes, Dr. Adler was unapologetic. He told the Associated Press in 1996 that, "I don't take responsibility for couch potatoes. They really should exercise."

Coming to America

Dr. Robert Adler was born on December 4, 1913 in Vienna, Austria to Max Adler, a prominent social theorist, and Jenny Hershmann Adler, a doctor. He received his doctorate in physics at the age of 24 from the University of Vienna in 1937.

Following Austria's annexation by Germany in 1939, Dr. Adler, a Jew, left the country. He traveled first to Belgium, then to England, where he acted on the advice of friends, who recommended that he emigrate to the United States.

Adler arrived in the U.S. in 1941, at which time he was hired by Zenith (known at the time as the Zenith Radio Corporation) to work in its research division. It was a common practice for companies like Zenith and RCA to fund their own state-of-the-art research facilities that were the equal of facilities such as AT&T's Bell Laboratories.

He settled in Chicago where the company maintained headquarters. He remained in Chicago the rest of his life, and continued to work for Zenith on and off for the next six decades.

In 1952, Adler was named associate research director. In 1963, he was named vice president and director of research. He retired in 1982, but continued to work for Zenith as a technical consultant until 1999 when Zenith was purchased by LG Electronics of South Korea.

According to John Pederson, a former Zenith vice president, Dr. Adler was not allowed to work on classified projects during the Second World War. So, the company set him up in a private laboratory with assistants to work independently on projects of his own choosing.

Despite the prohibitions that kept him from working on classified, wartime projects, Dr. Adler specialized in military communications equipment, and he came to be appreciated for his ability to see the wider applications of specific technology. Most of his later work, including the ultrasonic technology employed in the "Space Command" remote, grew out of his early research.

Peace

Adler concentrated his efforts on television technology after the war. His invention of the "gated-beam" vacuum tube was typical of the innovations that sprang from his fertile mind.

(Incidentally, the "gated-beam" tube was Dr. Adler's personal choice for the most significant innovation of his long and distinguished career.)

The "gated-beam" tube represented an entirely new concept in receiving tubes and sound circuitry. Not only did it improve sound quality by eliminating a lot of spurious noise and distortion, it simplified the design of sound systems in TV receivers, and reduced costs.

The electron beam parametric amplifier was another significant advance. Jointly developed in 1958 by Dr. Adler and Dr. Glen Wade of Stanford University, the amplifier was universally adopted by radio astronomers worldwide, as well as by the U.S. Air Force for long-range missile detection.

In 1966, Dr. Adler's work in acousto-optical interaction was behind the successful public demonstration during which a wall-sized television display was generated by, what was then, unconventional means. In place of a cathode ray tube, the team of Zenith engineers created the display by manipulating a laser beam.

In the early 1970s, Dr. Adler's research was instrumental in the development of the digital video revolution that exploded in the 1990s.

In recent years, he had been a prime mover behind the evolution of touch screens as a result of his work involving surface acoustic wave (SAW) technology, and as a consultant to firms such as Elo TouchSystems, a leading manufacturer of interactive touch screens at airport kiosks, museums, and elsewhere.

SAW technology is an integral part of a wide range of uses from television to video gaming to automated teller machines, and more. The technology is essential to our love-hate relationship with the cellular telephone.

Dr. Adler's research into SAW technology continued to the end of his life. His most recent patent application dealt with touch-screen technology and was published two weeks before he died.

Honors and Awards

A listing of the honors bestowed on Dr. Adler follows. By no means is it complete:

1951 - Elected Fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc. (IEEE) "for his development of transmission and detection devices for frequency modulated signals and of electro-mechanical filter systems."

1959 - Awarded the 1958 Outstanding Technical Achievement Award from IEEE for his "original work on ultrasonic remote controls" for television.

1967 - Awarded "Inventor-Of-The-Year" award by George Washington University's Patent Trademark and Copyright Research Institute "for his inventions in the field of electronic products, devices, and systems used in aircraft communications, radar, TV receivers and FM broadcasting."

1970 - Received the Consumer Electronics Outstanding Achievement Award, an honor given annually for significant contributions to the advancement of consumer electronics through engineering achievements.

1980 - Received the Edison Medal, the IEEE's principal award for recognition of career meritorious achievement.

1981 - Received Sonics and Ultrasonics Achievement Award from IEEE.

1998 - Co-Recipient (with Eugene Polley) of the Engineering Emmy Award from the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences for "pioneering work in the development of the remote control."

2000 - Inducted into the Consumer Electronics Hall of Fame by the Consumer Electronics Association for significant contributions to the consumer electronics industry.

2000 - Inducted into the National Academy of Arts and Sciences Chicago/Midwest Chapter's "Silver Circle" in recognition of individuals who have devoted 25 years or more to the television industry, and for significant contributions to Chicago broadcasting.

He was also a Fellow in The American Association for the Advancement of Science, as well as a member of The National Academy of Engineering.

He was uncommonly modest. In 1969, he was sent to Moscow as part of an IEEE delegation to the annual meeting of the Popov Society for Radioengineering, Electronics, and Communications. Prior to going he learned Russian in order to be able to present his paper in Russian as a gesture of goodwill to his hosts.

A Full and Complete Life

In his personal life, Dr. Adler immersed himself in the Chicago cultural scene. He supported the Art Institute of Chicago, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Masters of Baroque, and Community Theater.

For years, he ventured whenever possible to the Rockies to engage in mountain hiking during summer months, and skiing in winter. He was an avid downhill skier until the age of 89. He was a licensed pilot and an enthusiastic world traveler for both business and pleasure. Dr. Adler was fluent in English, German, and French.

Dr. Adler had no children. He is survived by his wife, Ingrid Adler, whom he married in 1998. His first wife, Mary, died in 1993.

Mike Daisy

AmericanInventorSpot.com

Sources:

American National Business Hall of Fame

Associated Press

Chicago Tribune

The Dead Media Project

Federal Reserve Bank

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The New York Times

Yahoo

Widescreen Review

Wikipedia

Zenith Corporation